By Bob Wood.

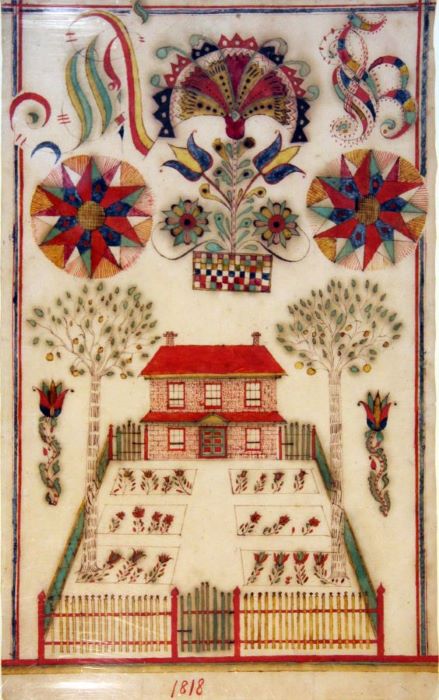

Today’s topic is the garden fence and the narrow garden beds that lay close along the fences of the early kitchen gardens.

The “PA Dutch” dialect was wholly unwritten, and what bits of information we have such as day books and journal accounts were written in German by men; while the garden, the woman’s domain, has gone mainly unnoted. Nevertheless we do know a good bit and much can also be reasonably inferred. Additionally, 20th century interviews with folk informants have provided valuable details.

The kitchen garden

It’s safe to say that beginning with settlement around 1720 most every house had a fenced kitchen garden. The house site itself may have been determined with an eye to the future garden. Near the eastern or southern side of the house the Dutchman wanted good, gently sloping ground. In addition to the kitchen garden there usually was an unfenced field “patch” where the necessarily large quantity of cabbages, turnips, potatoes and later sweet corn would be planted.

The fence

In the early 18th century, the garden site was usually fenced with four foot high boards, called pales, split from white oak, walnut, or usually chestnut logs. The fence was an absolute necessity as livestock roamed free.

Unlike the 4 or even 5 rectangular holes for rails cut into field fence posts, the garden fence post had only 2 slots for rails. One slot was 6 inches from the top, the other 6 inches from the bottom. The post itself was usually chestnut, hewn square with a broad axe, and planted firmly in the earth leaving about 4 feet and 4 inches above the ground. The posts were set 11 feet apart. Chestnut rails 12 feet long were cut, hewn flat on one side and inserted into the posts’ slots with the flat side out. This made an 11 foot panel of fence known in Pennsylvania Dutch as a gefach. Even into the 20th century, rail fence was bought and sold by the section or 11 foot panel.

As for the pales, in the very early days a chestnut log would be sawn into four foot sections and then quartered. The pales, really clapboards, would be split from the quarters using a froe and mallet producing rough boards about an inch thick. Sometimes one of the top corners of the boards would be cut off at a 45 degree angle giving a bit of “finish” to the otherwise crude fence. The pales’ width varied as they would have been split from various logs. Spaced about an inch apart, they were nailed onto the two horizontal rails Aside from labor, the expense of the fence was the nails, each nail having to be hand forged, usually by the blacksmith’s apprentice.

As fences evolved in the later 18th century, the rough pales gave way to sawn pickets, which in the 19th century were whitewashed every spring along with everything else around the farmyard.

Plantings

Within the garden, vegetable plantings were done on square or rectangular beds sometimes raised about six inches above the paths that surrounded them. An outside path ran around the whole garden interior about two feet from the fence. Between the fence and this path were narrow beds that didn’t get spaded in the spring. Here were the perennials: culinary herbs, medicinal herbs, woody perennials, and flowers.

Flowers were a must for every Pennsylvania German housewife. In the older gardens perhaps the narrow beds held a section of blumme land or flower bed. Since these beds were not spaded in the spring they held the perennials as well as some annuals. Researcher Alan Keyser has identified no fewer that fifty-one different flowers that could have been found in the old gardens. The whole list is too long to reproduce here but includes such favorites as dahlia, tiger lily, day lily, peony, hollyhock, sweet william, larkspur and hollyhocks.

Woody perennials include the bushy vines like black, orange, and red raspberries, currants, gooseberries, high blackberries, June berries, wormwood and even grape vines planted inside or just outside the fence and provided with a trellis. Many of these perennials form canes which could lean against or be tied to the fence.

Of the medicinal herbs there is seemingly no end. It has been said that in the old days, if a family member became sick the first thing the housewife tried was medicinal herbs and teas. If that didn’t work she might try the local braucher or as we would say “pow-wow” healer. If that didn’t work they went for the doctor as a last resort.

Many plants used as medicinal plants were not grown in the garden, but grew wild around the farmstead buildings. Still, there is a lengthy list of medicinal herbs that could be found in the narrow beds. Most of these were perennials. Some of the more common were borage, comfrey, feverfew, horehound, lambs ear (of which there were no fewer than 29 uses), lavender, pot marigold, sage, and many more.

It is important to keep in mind that gardens, their fences, and the plantings within changed over time so that a garden of, say, 1840 would be somewhat different from one of 1740.

Probably the best study to date of early garden plantings is “Plant Names and Plant Lore among the Pennsylvania Germans” by David E. Lick and Rev. Thomas R. Brendle, published by the Pennsylvania German Society in 1923.

Goschenhoppen Historian Bob Wood has researched, written and spoken extensively about PA Dutch folk culture topics and can be found at the Antes House during the Goschenhoppen Folk Festival.